As an undergraduate, our math department used Wolfram Research’s Mathematica heavily for instruction in a number of classes. Initially, I found it perplexing and frustrating. While most of my peers remained in that state (and never used it again after those classes), I soon found myself ordering and reading An Introduction to Programming with Mathematica.

Seven years later, I find myself using Mathematica almost daily. As a student, it is one of the most helpful tools at my disposal, and it has saved me countless hours of tedious computation by hand. I’m not sure I can express all the ways in which I appreciate it, but I hope to share some.

I admit that I primarily use Mathematica as a glorified calculator. Most of my code is single use code to help me with a homework assignment. I have written some longer code for class projects, but rarely more than a few hundred lines. However, for the work that I have had over the past seven years, it is exactly the right tool, and I don’t know of any other language which comprehensively offers all the features I need within its core language.

One other note to the Redditors and cynics (but I repeat myself): I’m not recommending or encouraging programmers to jump ship from their main languages to Mathematica. I’m not suggesting that Mathematica doesn’t have any shortcomings. I’m not arguing that Mathematica is good for everything. I’m well aware that Mathematica is an expensive, closed platform. I’m well aware that Mathematic has the worst undo ever. I’m not writing an advertisement or getting paid by Wolfram. I’m simply shared the story of a program that has become an invaluable part of my schooling.

1. Powerful Symbolic Computations

Perhaps the thing Mathematica is most well-known for is symbolic computations. The oldest Mathematica file I have on my computer is a single line of code that I apparently used on a differential equations quiz in 2005. In it, I did a partial fraction decomposition: the bane of calculus 2 students, but easy for a computer.

One of the benefits of Mathematica, is the elegance of typesetting in both the input and the output. Wolfram has taken great care to make Mathematica an aesthetically excellent experience, and I’m grateful for that.

These days, I avoid doing algebraic manipulations by hand at all costs. It’s not worth it to me to risk making errors that might trickle down into my work. I let computers handle such things for me. Thus, when I’m doing homework, I usually have a notebook open filled with one-off expressions like

Of course, it can solve much harder problems too. Integration is no problem. Here’s a triple integral I solved in my electricity and magnetism class sophomore year. (I wish I remembered what it all means.)

The output is messy because Mathematica tried to solve the integral as generally as possible. We can get a more clear answer by clarifying some assumptions we’re making about the parameters.

2. Functional Programming

Like R, Mathematica allows procedural programming.

However, again like R, Mathematica is really built for functional programming. Wolfram has a great tutorial on the topic, but let me share a brief example from my own use.

On a homework assignment this week, I wanted to measure the total tardiness for various schedules in a single machine problem. Each of the four jobs had a total processing time, given by {2,4,6,8}, and a due date {4,14,10,16}. The tardiness of a job for a given schedule (i.e. ordering of the jobs) is 0 if the job is completed on time and how late it is otherwise. First I set processing time and due dates for the four jobs:

Any permutation of the job indices {1,2,3,4} gives a valid schedule. Suppose we want to know the total lateness of the schedule x={1,4,3,2}. The ordering of processing times is given by p[[x]] so the time when each job is completed is a running total of the processing times:

The lateness of each job is defined by the completion time minus the due date:

To get the tardiness, we want the max of the lateness and zero. There are a number of ways to do this, but one is to apply a max function to each element of the list:

(The # and & are part of Mathematica’s notation for pure functions.) Or, more succinctly,

In a non-functional language, this would have required a for-loop and several lines of code. In a functional language, it naturally fits into a single line. Getting the total tardiness adds no more complexity:

since % returns the last line evaluated.

This is only a simple example of a functional operation in Mathematica. Expressions can become much more complex. All my Mathematica code is littered with functional expressions, but rarely will you see a for-loop or a while-loop in my code. And I like it that way.

Oh, and if you want to parallelize these operations: not a problem.

3. Optimization

As a student of operations research, I spend a lot of time solving optimization problems. Solving optimization problems of many flavors is built right into Mathematica. Solving linear programs given the matrices is easy with the LinearProgramming function. Because most of the problems I’ve solved up to this point have been “toy” problems for class, I can’t attest to Mathematica’s ability to handle large-scale problems, but they claim to be able to handle large problems. Mathematica’s ExampleData function gives easy access to many data sets, including NetLib.org’s LP problems. Mathematica could solve this problem with 6072 rows and 12230 columns in 60 seconds on my 11-inch Macbook Air.

The built-in solver certainly isn’t as robust as CPLEX or other commercial solver, but it does, at least, provide several solution methods.

I most often find myself using the Minimize and Maximize functions with explicit constraints:

In the future, I hope to do a post on using Mathematica as a pseudo-modeling language. You can see the documentation for a number of other optimization related functions.

Recently, I’ve been working with stochastic dynamic programming problems (i.e. Markov decision processes). Mathematica offers the easiest memoization I’ve ever seen in any language. Combined with functional aspects, I can solve dynamic programs with relatively little code.

4. Graphics

When I am doing school work, I want to be able to do complicated computations and then visualize the results quickly. Because of how tightly knit the native Mathematica graphics are built into the core language, I don’t have to go out of my way to do this.

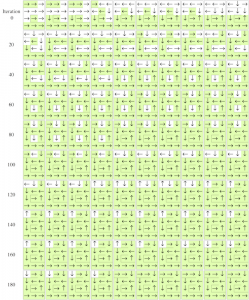

Last semester, I wanted to demonstrate a Monte Carlo algorithm for navigating a maze. Over 200 iterations, a relatively simple solver (built, of course, in Mathematica) could find an optimal path through a 4 by 3 maze. for a report I was writing.

Working straight from the output of the solver, in about twenty lines of code, I output a grid showing candidate solution every other iteration (the green cells indicate cells where the action is optimal). Followed by an Export function, the graphic was ready to be included in my  file. All of this without having to open another program or import any graphics packages.

file. All of this without having to open another program or import any graphics packages.

5. Documentation

Wolfram has been careful to write readable and thorough documentation for Mathematica. Though Mathematica is not free software, its 10,000+ pages of documentation are available online. Not only does the documentation for every function (usually including bullet points with Basic Examples, Scope, Generalizations & Extensions, Applications, Properties & Relations, and Neat Examples), it’s full of tutorials on various aspects of the language. Of you read the help inside of Mathematica, the files are simply notebooks, so the code can be evaluated within the documentation. I think you’d be hard pressed to find a language with better documentation.

6. Naming Conventions

If Mathematica wins one debate hands down, its naming conventions. By their own standards, “As with most Mathematica functions, the names are usually complete English words, fully spelled out.” If you know the mathematical name for something, you can probably guess the Mathematica form.

Stephen Wolfram wrote a blog post a few years ago on his personal role in naming Mathematica functions. Perhaps not too different from his late friend Steve Jobs, Wolfram desires intense control of the finest details of his products.

I just realized that over the course of the decade during which were developing Mathematica 6—and accelerating greatly towards the end—I spent altogether about 10,000 hours doing what we call “design reviews” for Mathematica 6, trying to make all those new functions and pieces of functionality in Mathematica 6 be as clean and simple as possible, and all fit together.

I think this has paid off.

Some people would complain about a language such an enormous number of named expressions, but Wolfram (the man and the company) have been so careful in constructing it that it doesn’t feel bloated.

7. Interactivity

In version 7, Wolfram introduced interactivity into Mathematica. The Manipulate function is one I have found extremely valuable. It allows you to parametrize an expression and adjust the parameters while seeing results in real-time. For example, you could use Manipulate to adjust the region over which a function is plotted:

A side benefit to the careful construction of the language is that functions with related behavior often have interchangeable expression lists. Manipulate can be replaced with Animate with no other changes.

Or Table for that matter:

8. Continual Development

Thankfully, Wolfram hasn’t given up on Mathematica. It’s been in development now for nearly 24 years. Mathematica 7 (released in November 2008) introduced interactivity features, access to many data sets, and built-in parallel computing, among other things.

Mathematica 8, released in November 2010, brought integration with Wolfram Alpha and free form input. I find myself using this frequently when I’m teaching calculus. For example:

Mathematica 8 also brought incredible probability computations. What’s the probability that a standard normal random variable is less than a Uniform(0,1) random variable? No problem.

The list of things new in version 8 goes on.

9. Comprehensiveness

A feature of Mathematica that is hard to articulate is the comprehensiveness of the features I’ve already mentioned plus many more. It’s a full featured programming language, but the core language also extends to the depths of applied and pure mathematics. Symbolic manipulation? Check. Numerical methods? Check. Abstract algebra? Check. Graph theory? Statistics? Visualization? Optimization? String Processing? Differential equations? Computational chemistry? Calculus? Check. Check. Check.

The comprehensiveness of Mathematica’s functionality along with dynamic typing and functional programming allows me to write code to do complicated tasks very quickly. I love it.

Conclusion

No doubt, Mathematica has its limitations1: Worlds worst undo. Not object-oriented. Closed platform. Expensive. No autosave. No data frame structure.

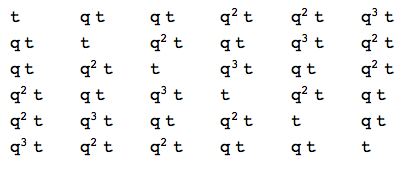

However, for me, it’s an invaluable tool. Last semester, I saw a less computer savvy fellow graduate student writing out a huge table by hand. I don’t recall the name of what he was doing, but it was something to do with measuring the distance between permutations. I told him I could do it for him in a single line of Mathematica.

In just a few minutes I wrote him the following code. It ended up taking me more than one line, but I wrote the code much faster than he was generating it by hand. (His table was actually for the 4-permutation case, so it was 24x24 instead of 6x6.)

Using Mathematica for little things like this. It allows me to spend my time and brain power on the things that computers can’t handle.

I love Mathematica. And maybe you will too.

(I wrote this post in Mathematica. You can check out the notebook here.)

I might follow with a post on that very point ↩︎